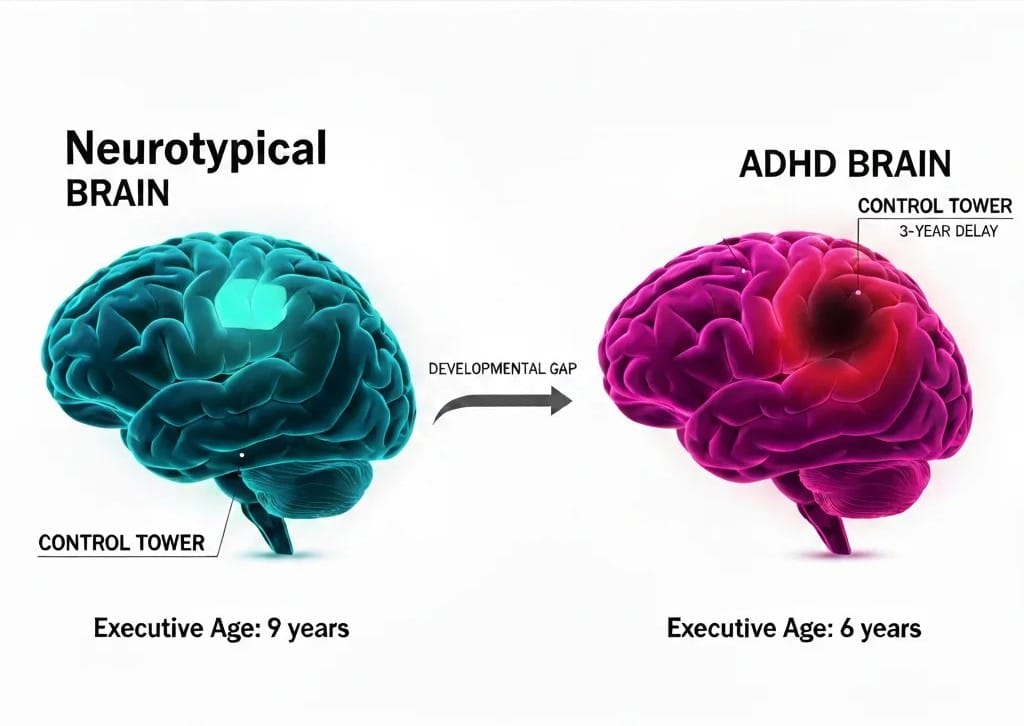

Many parents notice that their child with ADHD may be intelligent and capable, yet struggle with emotional regulation and behavior in ways that seem younger than their peers. This occurs because ADHD brain maturity delay is associated with a developmental lag of up to three years in executive function skills.1

The ADHD brain follows a standard developmental journey, but on a slower schedule. This means the prefrontal cortex—the brain’s “Control Tower” for attention, impulse control, and emotional regulation—simply reaches maturity later.

By applying the Rule of Two-Thirds (30% Rule), parents can estimate a child’s “Executive Age” (Chronological Age × 0.67) to provide the right support at the right time. In this article, Dr. Amit Pande (PhD) explains the science behind ADHD brain maturity delay and how parents can guide their child’s development with patience and confidence.

⚡ Executive Summary: The ADHD Development Gap

If you are short on time, here are the key insights into how ADHD affects brain maturity:

- The 3-Year Lag: The prefrontal cortex, the brain’s “Control Tower,” often matures about 2 to 3 years later in children with ADHD than in their peers.

- Intelligence ≠ Maturity: A child can have a high IQ but the emotional control of someone years younger.

- The Rule of Two-Thirds: Multiply your child’s age by 0.67 (Age × 0.67) to estimate their “Executive Age” and set realistic expectations.

- A Shifted Timeline: ADHD brains are not broken; they follow the same developmental path, just at a slower pace, often continuing to mature into the late 20s.

- Scaffolding Is Key: Because the internal control system is still developing, external supports such as routines, visual cues, and reminders help bridge the gap.

What Is ADHD Brain Maturity Delay?

It is important to understand the biological reality behind why a child with ADHD may act younger than their age. The answer is ADHD brain maturity delay, a slower development of the prefrontal cortex — the brain’s “Control Tower” for attention, impulse control, and emotional regulation.

This specific region is responsible for what scientists call Executive Functions: the mental skills that manage attention, impulse control, and emotional regulation.2

In all children, the prefrontal cortex is the last part of the brain to fully mature, often continuing into the early to mid-twenties. In ADHD, however, this “construction” follows a slower, shifted timeline.3

A landmark 2017 study found that, on average, children with ADHD have slightly smaller total brain volume and may take longer to reach full maturity compared with their peers.4

Multiple studies suggest that ADHD may delay executive function development by two to three years.1, 5 , 6

Because this control system is still under construction, a child may struggle with:

- Emotional Regulation: Staying calm under stress

- Impulse Control: The “braking system” that helps a child pause before acting

- Executive Function: Planning, organizing, and starting tasks

Signs of Brain Maturity Delay in ADHD

Parents often notice that their child’s behavior feels “younger” than their age. These everyday struggles reflect the delayed development of the prefrontal cortex:

- Emotional Regulation: Frequent meltdowns or difficulty calming down after minor stress.

- Social Preferences: Often preferring the company of younger children, because their play style feels more comfortable and aligned with your child’s pace.

- Low Frustration Tolerance: Giving up quickly on hard tasks or frequent “I can’t” moments.

- Impulse Control: Acting before thinking, blurting out, or having trouble waiting for a turn.

- Executive Lag: Forgetting school materials, losing items, or struggling to follow multi‑step instructions.

- Delayed Internal Dialogue: Limited ability to “talk themselves through” a problem silently.

These are not signs of laziness or defiance—they show that the brain’s “Control Tower” is still under construction and simply maturing on a slower schedule.

The Science: Cortical Thickness and the 3-Year Lag

To understand why children with ADHD may show delayed maturity, scientists use 3D MRI scans to measure Cortical Thickness.7 This term describes how the brain’s outer layer grows, strengthens, and refines over time.

Research shows that while neurotypical children typically reach peak cortical thickness around age 7, children with ADHD often reach this milestone later, closer to age 10.8 However, the maturation process, in the prefrontal cortex continues until the mid-to-late twenties.9

It is important to remember:

- The Developmental Path is the Same: Children with ADHD follow the same journey as their peers; their timeline is simply shifted.9

- Full Maturity Still Happens — Just Later: The brain reaches full efficiency, but maximum maturity arrives later than in neurotypical children.

This explains why a child may be intellectually bright yet struggle with the everyday maturity expected of their age. Understanding this difference helps parents see challenges as developmental, not intentional.

Why IQ Does Not Match Maturity

A common question parents ask is, “My child is so smart, why can not they act their age?”

It’s important to remember that ADHD brain maturity delay does not affect intelligence. A child may be a gifted reader or strong in math (their IQ), yet still forget their school bag every single day (their executive age). This gap is where many families feel stuck.

By applying the Rule of Two‑Thirds, you can recalibrate expectations so their intelligence can shine while their executive skills gradually catch up.

The Rule of Two-Thirds (30% Rule): Understanding Your Child’s “ADHD Executive Age”

To explain the gap between a child’s chronological age and their real-world behavior, experts such as Dr. Russell Barkley describe the ADHD 30% Rule, often referred to as the Rule of Two-Thirds.10

This rule suggests that children with ADHD experience about a 30% delay in executive function skills. A child may be intellectually bright, yet their ability to manage time, emotions, and tasks often functions at about two‑thirds of their chronological age.

For example, a nine-year-old with ADHD may function more like a six-year-old in areas of impulse control, planning, and self-regulation.

How to Calculate It:

To find your child’s “Executive Age,” take their chronological age and multiply it by 0.67.

- 9 years old × 0.67 ≈ 6 years old

- 12 years old × 0.67 ≈ 8 years old

- 15 years old × 0.67 ≈ 10 years old

This number reflects executive function age, not intelligence.

Brain imaging studies show a 2–3 year delay, while the 30% Rule gives parents a practical tool for everyday life. The gap can appear larger in older children and teens because expectations rise faster than the brain’s delayed timeline.

ADHD Development Gap Examples

Chronological Age Estimated Executive Age What You Might Notice 6 years 4 years Difficulty waiting turns, frequent emotional outbursts 9 years 6 years Needs help starting homework, forgets instructions 12 years 8 years Struggles with organization and time management 15 years 10 years Impulsive decisions, inconsistent self‑control

Note: This table is a guide, not a strict rule. Every child is different.

Why This Matters

If you expect a nine-year-old with ADHD to behave like a typical nine-year-old in emotional control, you may feel constant frustration. However, if you understand their executive skills are closer to age six, your approach naturally shifts.

As a result, you may:

- Give shorter instructions

- Provide more reminders

- Break tasks into smaller steps

- Offer structured routines

- Stay calmer during emotional outbursts

The Catch‑Up Myth: Is This Delay Permanent?

A common fear for parents is: “Will my child always be behind?” The short answer is no. While ADHD is a lifelong neurological condition, the developmental gap is a temporary timing issue.

As a molecular biologist, I explain to parents that ADHD is not a “broken” brain—it is a brain on a different schedule. The processes of myelination (insulating the brain’s wiring for speed) and synaptic pruning (trimming unnecessary connections) simply follow a delayed timeline.

Structural Maturity vs. ADHD Wiring

By the late 20s, the ADHD brain finally reaches full structural maturity. This “catch-up” period continues well into the mid-to-late 20s, whereas neurotypical brains often stabilize around age 21 or 22.8

At this stage, the hardware of the brain is fully built. While an individual will always have an ADHD brain—meaning they may remain naturally prone to distractibility—they finally have the mature neurological “braking system” needed to manage those traits effectively.

What Changes as They Grow?

As the brain matures, the gap often begins to narrow. However, it can look different at each stage of life:

1. In Adolescence (The Peak of the Gap)

The gap often feels the widest here. While peers are gaining independence, a teen with ADHD still requires significant “External Brain” support.

They may have the physical body and social desires of a 16-year-old, but the impulse control and organizational skills of a 13-year-old. This is the stage where they need “scaffolding” the most—not because they are rebellious, but because their brain wiring is under maximum pressure.

2. In Early Adulthood (The “Click” Moment)

Many young adults find their executive skills begin to “click” in their mid-20s. This is the biological “catch-up” period where the prefrontal cortex finally reaches its full processing power.

You will likely see a surge in their ability to manage their own schedules and regulate emotions. During this time, they often move from needing your reminders to using their own compensatory strategies, like digital alerts, planners, and structured routines.

3. In Adulthood (Full Maturity at Age 28–30)

By the time the brain reaches full maturity, the developmental lag usually stabilizes. While traits like distractibility may remain, the maturity “gap” disappears.

Most adults with ADHD learn to choose careers that highlight their strengths—such as creativity, high energy, or crisis management—rather than focusing on their executive weaknesses.

Practical Strategies: How to Support a Child with Brain Maturity Delay?

When we understand that a 12‑year‑old with ADHD may have an “Executive Age” closer to 8, our parenting toolkit changes. Instead of punishing the 12‑year‑old, we begin supporting the 8‑year‑old within them.

Here are 8 practical strategies to support your child’s development using the Rule of Two‑Thirds (30% Rule):

1. Match Expectations to Executive Age

If your 10‑year‑old functions more like a 7‑year‑old in planning and impulse control, adjust accordingly.

- Supervise homework more closely

- Pack school bags together

- Give step‑by‑step guidance instead of broad instructions

This doesn’t lower long‑term goals—it simply provides the support a younger child would need right now.

2. Use External Structure Generously

Children with ADHD often struggle to stay organized on their own. External systems make life easier.

- Use visual schedules and checklists.

- Set timers for tasks.

- Keep routines consistent.

Structure reduces stress and helps behavior improve naturally.

3. Break Tasks Into Smaller Steps

Large instructions like “Clean your room” can feel overwhelming. Break them down into manageable parts:

- Put books on the shelf

- Place clothes in the laundry basket

- Make the bed

Smaller steps feel manageable and reduce resistance.

4. Teach Skills, Do not Assume Them

Children with ADHD often lag in executive skills, and these abilities do not simply “click” on their own—they must be taught, modeled, and practiced step by step.

Examples of skills to teach:

- Using a planner: show them how to write down tasks and check them off

- Pausing before reacting: practice taking a breath before responding

- Problem‑solving after mistakes: guide them to ask, “What can I do differently next time?”

- Calming strategies: rehearse simple tools like deep breathing or squeezing a stress ball

Practice these skills during calm, everyday moments—not in the middle of a meltdown.

5. Stay Calm During Emotional Storms

Emotional outbursts are usually a sign of delayed regulation, not defiance. Try these simple steps:

- Lower your voice: a calm tone helps ease big emotions.

- Validate their feelings first: let them know it’s okay to feel upset.

- Offer a short reset break: give them space to regain control.

Your calm nervous system helps guide theirs back to balance.

6. Use Scaffolding, Then Step Back

Scaffolding is like temporary support around a building—it’s there while the structure is growing, then removed once it’s strong. Children with ADHD often need this kind of support as they learn new skills.

Examples of scaffolding:

- Sit beside them during homework

- Remind routines daily

- Help organize materials

As their skills improve, gradually step back. The goal is to give just enough help at first, then reduce it so they can practice independence.

7. Reinforce Effort, Not Just Outcome

Children with ADHD often hear more correction than positive feedback. That’s why it’s important to notice the effort they make, even if the job is not finished perfectly.

Celebrate effort when your child:

- Starting a task on their own

- Pausing before reacting

- Remembering one step without being reminded

Recognizing these small wins builds confidence and strength.

8. Protect Sleep, Movement, and Nutrition

Healthy routines strengthen emotional control and attention. When these basics are steady, children with ADHD have more energy to focus and regulate themselves.

Key habits to protect:

- Consistent sleep schedules

- Daily physical activity

- Balanced meals

- Limited late‑night screen time

When parents prioritize these routines, children feel calmer, stay more focused, and handle daily challenges with greater confidence.

The Takeaway

ADHD brain maturity delay does not mean a child is lazy, undisciplined, or broken. It means their brain is developing on a different timeline. By understanding the Rule of Two-Thirds and recognizing your child’s Executive Age, you can shift from frustration to empathy.

The most important message is this: Your child will catch up. With patience and structure, you are not just managing behavior. You are creating the environment their brain needs to grow, strengthen, and function independently.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What is ADHD brain maturity delay?

ADHD brain maturity delay refers to a slower development of the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s “Control Tower” for attention, impulse control, and emotional regulation. This delay can create a developmental lag of up to 2–3 years compared to peers.

Q2: Does ADHD brain maturity delay mean my child is less intelligent?

No. ADHD affects executive function skills, not intelligence. A child may be academically advanced yet still struggle with planning, organization, or impulse control.

Q3: How can I calculate my child’s “executive age”?

Experts use the Rule of Two‑Thirds (ADHD 30% Rule). Multiply your child’s chronological age by 0.67 to estimate their executive age. For example, a 9‑year‑old may function more like a 6‑year‑old in self‑regulation.

Q4: Is ADHD brain maturity delay permanent?

No. ADHD brain maturity delay is a shifted timeline, not a permanent deficit. ADHD brains are not broken. They follow the same developmental path, just at a slower pace, often continuing to mature into the late 20s.

Q5: How can parents support a child with ADHD brain maturity delay?

Parents can scaffold skills by breaking tasks into smaller steps, using visual schedules, offering reminders, and adjusting expectations to match executive age. Empathy and structure are key.

Q6: Why does my child seem smart but act younger than their age?

This mismatch happens because intelligence (IQ) and executive function develop on different timelines. ADHD delays executive skills, so a child may excel academically but struggle with everyday maturity.

Q7: Can ADHD brain maturity delay improve with support?

Yes. Thanks to neuroplasticity, the brain can adapt and grow. Consistent routines, positive reinforcement, and scaffolding strategies help children strengthen executive skills over time.

References

📚 Click to view references

- National Institute of Health (NIH). (2014, September). Focusing ADHD: How the Brain Manages Attention. View Source (NIH)

- Deshmukh MP, Khemchandani M, Thakur PM. Exploring role of prefrontal cortex region of brain in children having ADHD with machine learning: Implications and insights. Appl Neuropsychol Child. 2026 Jan-Mar;15(1):71-83. View Source (PubMed)

- Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Dec 4;104(49):19649-54. View Source (PMC)

- Hoogman M, Bralten J, Hibar DP, et al. Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with ADHD in children and adults: a cross-sectional mega-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;4(4):310-319. View Source (PMC)

- Shaw et al. (2007). Attention‑deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. View Source (PubMed)

- Sadozai, A.K., Sun, C., Demetriou, E.A. et al. Executive function in children with neurodevelopmental conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat Hum Behav 8, 2357–2366 (2024). View Source (Nature)

- Fujita S, Hagiwara A, Hori M, et al. 3D quantitative synthetic MRI-derived cortical thickness and subcortical brain volumes. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019 Dec;50(6):1834-1842. View Source (PubMed)

- Berger I, Slobodin O, Aboud M, et al. Maturational delay in ADHD: evidence from CPT. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013 Oct 25;7:691. View Source (PMC)

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2007). Brain matures a few years late in ADHD, but follows normal pattern. View Source (NIMH)

- Barkley, R. A. (2012). This is how you treat ADHD based on science. Keynote lecture at the 2012 Burnett Seminar. Watch Video (YouTube)